“Our research has shown that an Optimized Shrub System (OSS) results in improved nutrient and water availability, and ultimately increased yields”

The Situation

The semi-arid region of the West African Sahel is primarily dependent upon rain-fed agriculture to feed a growing population that is projected to double in the next 30 years.

This dependence on climate related activities is a major factor contributing to the region’s vulnerability as 80% of the rural populations’ standard of living is linked to the performance of rain-fed agriculture with less than 5% of the land under irrigation.

In rain-fed agricultural regions with erratic rains, rainfall is both a critical input and a primary source of risk and uncertainty. In the Sahel, the rainy season is short and varies in length, with the number of rainy days varying from year to year.

High evaporation losses (up to 50%) of annual rainfall and a dominance of sandy soils with low water holding capacity, result in chronic soil water shortages during the growing season.

This variability is exacerbated by a changing climate where the temperatures are increasing, and more frequent in-season drought leads to crop water stress resulting in reduced yields.

This situation is further aggravated by severe soil degradation resulting from decades of poor land management practices. This combination of variability of rainfall and degraded soils causes persistent food insecurity as the regions’ resource-poor smallholder farmers struggle to feed the rapidly growing population.

The region is in desperate need of nature-based agricultural systems that maximize water use efficiency, provide improved yields as well as soil conservation using locally available resources that don’t rely on expensive chemical fertilizers and designer seeds.

Dramatic growth response of millet grown intercropped with Gueira senegalensis

The Solution

Fortunately, a shrub-intercropping system has been scientifically validated that meets the ecological and food security challenges of the Sahel based on two shrubs that dominate and co-exist with crops throughout; Guiera senegalensis and Piliostigma reticulatum, but their densities are low.

Although farmers recognize the value of shrubs, they typically coppice them in the spring to clear fields and unfortunately burn the residue, depriving soils of needed organic inputs.

Our research, funded by the National Science Foundation, has shown that an Optimized Shrub System (OSS) where shrub density is increased from current levels (<200-35 shrub/ha) to ~1500 shrubs/ha combined with annual incorporation of coppiced shrub biomass results in: improved soil quality, carbon (C) sequestration, greater microbial diversity and activity,

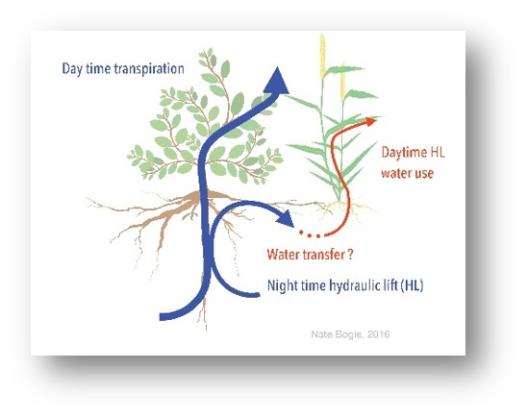

improved nutrient and water availability, and ultimately increased yields – up to three-fold (28+ peer reviewed articles). A truly remarkable finding is that the shrubs “bio-irrigate” crops via hydraulic lift at night, which combined with improved soil quality, significantly reduces crop water stress during in-season drought.

To Learn More, Please Visit: www.agroshrub.org.

You can also visit the West African Shrub Initiative website to learn more about the project.